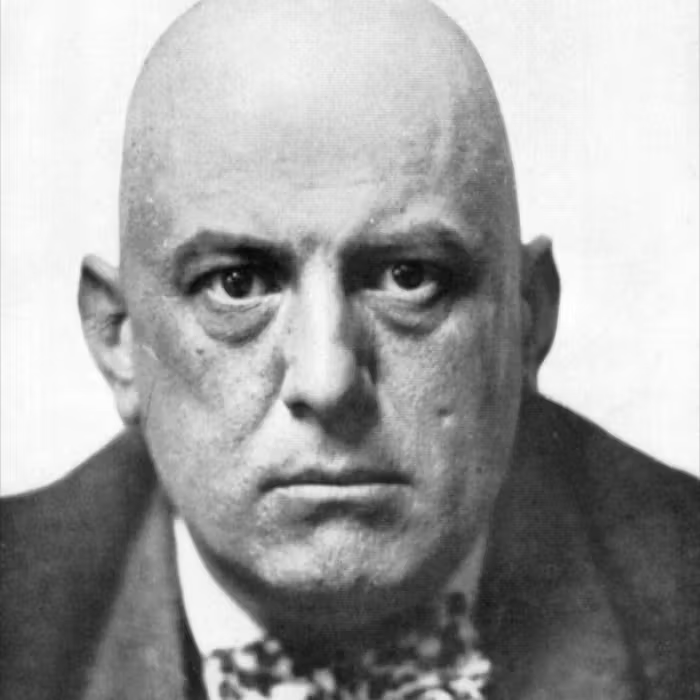

Aleister Crowley (1875–1947) remains one of the most infamous, controversial, and influential figures in modern occultism. A poet, ceremonial magician, mountaineer, and mystic, he reshaped Western esotericism through his creation of Thelema, his unique interpretation of Hermeticism, and his radical approach to spiritual freedom.

He also pissed off nearly everybody he crossed paths with, got kicked out of Italy by Mussolini, and was also the self-proclaimed prophet of The New Aeon. Oh, and most of this all took place almost a century ago.

To his admirers, he was a prophet of a new age. To his critics, he was “the wickedest man in the world.” Today, Crowley is seen as a foundational figure for nearly every strand of modern occult practice. But controversy still dogs his image, obscuring the rather unprecedented amount of magical texts, treatises, books, and articles he published during his life.

Early Life and Break from Christianity

- Born Edward Alexander Crowley in 1875 in Leamington Spa, England

- Raised in a wealthy but strict Plymouth Brethren household

- His father’s death in 1887 became a spiritual turning point

- Rejected Christianity as hypocritical, turning instead to mysticism, poetry, and philosophy

At Cambridge University, Crowley lived a life that was already moving far beyond the constraints of his strict religious upbringing. Though nominally studying philosophy before switching to English literature, he devoted far more time to personal passions than to academic requirements.

He quickly established himself as an eccentric, becoming president of the university chess club, writing poetry for student publications, and pursuing mountaineering with a serious commitment that earned him recognition in the Alpine climbing community.

By his early twenties, he had already climbed major peaks in the Alps—including the Jungfrau and the Eiger—often without guides, and was considered a rising talent among British climbers.

It was also during this period that Crowley began to embrace a life of open sexual exploration, rejecting the moral strictures of Christianity. He engaged in affairs with both men and women, at a time when homosexuality was still criminalized in England.

His relationships were often passionate but short-lived, including a formative romance with Herbert Charles Pollitt, a student actor and president of the Cambridge Footlights. Although they eventually separated due to Pollitt’s lack of interest in occultism, Crowley never forgot him, and the relationship is thought to have influenced Crowley’s growing understanding of sexuality as a spiritual force.

Alongside his mountaineering and romantic pursuits, Crowley was reading voraciously, immersing himself in philosophy, mysticism, and the growing occult literature available at the time. He studied works by Éliphas Lévi, Karl von Eckartshausen, and A.E. Waite, whose The Book of Black Magic and of Pacts helped awaken his serious interest in ritual magic.

In 1896, while traveling in Stockholm, Crowley experienced what he described as a profound mystical vision, possibly catalyzed by a sexual encounter, that he later regarded as his first authentic brush with spiritual illumination. The experience convinced him that he had a mystical destiny, and his search for a system to contain and direct this experience soon led him into the orbit of ceremonial magic.

By 1898, Crowley was introduced through Julian Baker and George Cecil Jones to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the most important occult society in England at the time. Founded by Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers, William Wynn Westcott, and William Robert Woodman, the Golden Dawn combined Hermeticism, Qabalah, Rosicrucianism, alchemy, astrology, and ceremonial ritual into a comprehensive magical system.

It was here, at last, that Crowley found a structure capable of channeling his restless energy and ambition. Initiated into the Outer Order at the Isis-Urania Temple in London, he took the magical name Frater Perdurabo, meaning “Brother, I shall endure to the end.”

Almost immediately, he threw himself into the practices with the intensity that would characterize his entire career. Under the guidance of Allan Bennett, one of the Order’s most skilled magicians, Crowley learned the intricacies of ceremonial magic, meditation, and the ritual use of magical invocations.

He experimented with the Goetia, or the evocation of spirits, and began to explore the Golden Dawn’s system of astral travel and inner plane work. Bennett also introduced him to the use of psychoactive substances as an aid to magical practice, something that would continue to play a controversial role in Crowley’s spiritual experiments.

Despite his rapid advancement, Crowley’s personality and lifestyle quickly set him at odds with many members of the Order. His bisexuality and open libertinism scandalized some of the more conservative members, including the poet W.B. Yeats, who regarded him as a destabilizing influence.

When the London temple resisted advancing him to the Second Order—the inner circle where the most secret teachings were transmitted—Crowley appealed directly to Mathers in Paris, who admitted him personally. This maneuver inflamed tensions within the Order and contributed to the bitter schisms that ultimately destroyed the Golden Dawn.

In these years, Crowley acquired not only the ceremonial and symbolic framework that would underpin his later work but also his enduring distrust of rigid hierarchy and institutional control within spiritual orders.

For him, magic was not about obedience or tradition for its own sake; it was about the direct pursuit of spiritual realization and the liberation of the True Will. The Golden Dawn gave him the tools, but it also taught him, through conflict, that the deeper work of Hermeticism required an uncompromising personal commitment beyond the politics of any single order.

The Golden Dawn and Frater Perdurabo

Crowley’s initiation into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn marked both his rise as a magician and his first major brush with esoteric controversy. Taking the name Frater Perdurabo, “Brother, I shall endure to the end”, he threw himself into the Order’s elaborate system of ritual and symbolism.

Under the tutelage of leaders such as Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers and Allan Bennett, Crowley studied the Golden Dawn’s synthesis of Hermetic Qabalah, ritual magic, alchemy, astrology, and astral work. He was a quick and ambitious student, absorbing the practices with an intensity that set him apart, and he soon demonstrated remarkable skill in ceremonial workings.

Yet Crowley’s character was as disruptive as it was brilliant. His open bisexuality, libertine behavior, and confrontational manner clashed with the sensibilities of many fellow initiates, particularly the poet W.B. Yeats, who saw him as reckless and unfit for spiritual advancement.

When the London temple refused to initiate him into the Second Order—the inner circle where the Order’s deepest teachings were transmitted—Crowley bypassed their authority and appealed directly to Mathers in Paris. Mathers, recognizing his potential, admitted him personally.

This move ignited a firestorm within the Golden Dawn. The London members, already resentful of Mathers’ autocratic leadership, viewed Crowley as the last straw. A dramatic schism followed, with factions battling over authority, legitimacy, and access to the Order’s sacred vault.

Though Crowley was not the sole cause of the Golden Dawn’s collapse, his presence and defiance crystallized the divisions that would ultimately tear it apart.

The episode left a lasting impression on him. Crowley had tasted both the power of ritual initiation and the pettiness of esoteric politics, and he drew an important conclusion: magical orders should exist not to enforce hierarchy, but to serve the awakening of the True Self.

This conviction shaped the founding of his own orders, the A∴A∴ and later his reforms of the Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.), where the focus was not obedience to leaders but the discovery of True Will—the divine purpose unique to each individual.

The Cairo Revelation: The Book of the Law (1904)

In 1904, while honeymooning in Cairo with his wife Rose Edith Kelly, Crowley underwent what he would later describe as the defining mystical revelation of his life.

The couple had rented an apartment near the Bulaq Museum, where Rose began falling into spontaneous trances, insisting that “they are waiting for you.” At first skeptical, Crowley came to believe she was channeling a spiritual intelligence connected to the Egyptian god Horus.

On March 20th, she led him to the museum and pointed to the Stele of Ankh-ef-en-Khonsu, a funerary tablet whose catalog number happened to be 666—a number Crowley had already embraced as his own symbolic identity, “The Beast.”

Shortly thereafter, on April 8th, 9th, and 10th, Crowley claimed to hear the voice of a disembodied intelligence named Aiwass, who dictated to him what became known as Liber AL vel Legis (The Book of the Law).

Over three days, Crowley wrote down the text in a state of trance, convinced that it was not his own composition but a revelation from a higher, supra-human source.

📖 Liber AL vel Legis (The Book of the Law) declared:

- Humanity had entered a new era, the Æon of Horus, a time of spiritual independence and self-realization, replacing the old age of dogmatic religion.

- The central law of this new aeon was: “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” Far from license or mere indulgence, this meant discovering and living one’s True Will—the divine purpose uniquely assigned to every soul.

- Each man and woman is a star, a luminous being moving according to its own orbit, harmonized with the greater order of the cosmos.

At first, Crowley resisted the text, unsettled by its uncompromising tone. He even set it aside for several years, unsure whether to embrace it.

But eventually, he came to see The Book of the Law as the cornerstone of his mission: a declaration that the end goal of spiritual practice was not submission to external authority, but union with the divine through the realization of True Will.

From this revelation was born Thelema, Crowley’s spiritual philosophy and religion, which redefined Hermeticism for the modern world and remains his greatest legacy.

Thelema: Crowley’s Religion of Will

At its heart, Thelema was Crowley’s attempt to gather the wisdom of East and West, ancient and modern, into a single living system for spiritual transformation.

Drawing upon Hermeticism, ceremonial magic, yoga, Qabalah, and mystical philosophy, Crowley shaped a path that he believed was perfectly suited to the dawning Æon of Horus—an age of individual freedom and direct communion with the divine.

Thelema is not a religion of blind obedience, but one of inner discovery. It insists that each individual carries within them a divine blueprint, a path of destiny known as the True Will.

To live according to this Will is not to indulge in whim or impulse, but to align oneself with the very rhythm of the cosmos, just as a star follows its own orbit without conflict or confusion.

Central to this process is the realization of the Holy Guardian Angel, a term Crowley used to describe the higher self—the intimate guide that bridges the human soul and the divine.

For Crowley, establishing conscious communion with this presence was the true initiation, the moment when the magician moves from theory to direct experience of the sacred.

This work of alignment and realization was what Crowley and the Hermetic tradition called the Great Work: the spiritual alchemy of transforming the ordinary human personality into a vessel of divine consciousness.

It was not simply about ritual or mystical ecstasy, but about the total integration of body, mind, and spirit into harmony with the universal order.

The primary tool of this path was Magick, which Crowley defined as “the Science and Art of causing Change to occur in conformity with Will.”

To him, Magick was not superstition or theatrics—it was a disciplined, experimental approach to spirituality, equally capable of reshaping the inner world of the psyche and the outer circumstances of life.

By synthesizing these elements, Crowley reframed the end goal of Hermeticism. No longer was it merely about mystical union in the abstract; it was about the living realization of one’s True Will, the discovery of the divine purpose encoded within, and its full expression in the world. In this sense, Thelema stood as both a continuation of Hermetic philosophy and its radical renewal for the modern age.

Orders and Communities

- A∴A∴ (1907): Founded with George Cecil Jones to spread Thelema and guide initiates through spiritual advancement

- Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.): Crowley became head of its British branch in 1912, introducing sex magic as a central practice

- Abbey of Thelema (1920–1923): An experimental commune in Sicily, combining ritual, creativity, and libertine living. It scandalized the press and was shut down by Mussolini’s government

Magick: Crowley’s System of Practice

Core Elements:

- Ritual & Ceremony (Golden Dawn-style invocations, Qabalah)

- Yoga & Meditation (from Hindu and Buddhist traditions)

- Sex Magick (using sexual energy for spiritual aims)

- Alchemy of the Self (psychological integration, union with higher consciousness)

Aleister Crowley’s practice of Magick, deliberately spelled with a “k” to distinguish it from stage illusions, has become one of the most enduring and controversial aspects of his legacy. He defined it as “the Science and Art of causing Change to occur in conformity with Will”.

This definition captures his view of magic as something precise, deliberate, and repeatable rather than superstitious or fantastical. To Crowley, Magick was a spiritual technology. It combined ritual, meditation, symbolism, and discipline into a coherent system designed to awaken the practitioner to their True Will, the divine purpose that exists in harmony with the universe.

Unlike many of his contemporaries who treated magical traditions as secret lore to be preserved, Crowley approached Magick as an evolving science. He began with the foundation laid by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, but he was never content to simply reproduce what he had been taught.

Through ceaseless experimentation, he refined and restructured existing rituals, producing original practices such as the Star Ruby, which he envisioned as a modernized banishing rite. This ritual, still used by magicians today, shows his emphasis on clarity, dramatic symbolism, and the psychological impact of ceremonial gestures.

Crowley believed that symbols, invocations, and ritual actions worked by bypassing the rational mind and speaking directly to the unconscious, a view that foreshadowed insights later developed in Jungian psychology.

His experiments extended beyond Western traditions. Crowley studied yoga, pranayama (breath control), and meditation while traveling in India and Ceylon. He integrated these practices into his system, treating Eastern methods of concentration and discipline as essential tools for the Western magician.

At the same time, he expanded the use of Hermetic Qabalah, alchemy, Enochian magic, and astrology, creating a global synthesis that drew from multiple streams of mystical thought. His work demonstrated that mystical attainment was not dependent on heritage or divine election but on method and practice.

Sexuality was another of Crowley’s radical contributions. He argued that sexual energy was one of the most potent forces in existence, capable of transforming consciousness and fueling magical results.

Through what became known as sex magick, he taught that erotic acts could be consciously directed toward spiritual goals, whether through solitary practice, same-sex ritual, or heterosexual union. In this, he reinterpreted one of the oldest Hermetic ideas—that spirit and matter are not opposed but united—into a living sacrament of the body.

Crowley was also a prolific writer who sought to codify his system in detail. Texts such as Book Four, Magick in Theory and Practice, Liber 777, and The Equinox serve both as instructional manuals and as records of his evolving thought. His style was intentionally dense and layered with symbolism, often designed to test the patience and persistence of the reader.

Yet beneath the obscurity lies a consistent message: Magick is not about belief but about direct experience, careful observation, and verification through practice. He urged his students to record their results as if they were conducting scientific experiments, maintaining detailed magical diaries that could be analyzed for consistency and progress.

Some of Crowley’s most famous workings illustrate both the ambition and extremity of his approach. The reception of The Book of the Law in Cairo in 1904 introduced the philosophy of Thelema, which placed True Will at the center of spiritual life.

His dramatic evocation of Choronzon in the Algerian desert in 1909 symbolized his confrontation with the fragmented and chaotic parts of the psyche, a trial that he claimed marked his initiation into higher states of attainment. His partnership with Victor Neuburg led to a series of rigorous magical retreats, where physical austerity and intense ritual work were used to strip the mind of illusion and force contact with deeper realities.

Among the lasting structures he created were new ritual forms, including eucharistic ceremonies such as the Gnostic Mass, which presented Magick not only as an individual discipline but also as a collective religious experience. By blending ceremonial magic with liturgy, Crowley gave Thelema a living ritual framework that continues to be practiced by Thelemic groups and branches of the Ordo Templi Orientis.

Controversies and Scandals

- Called “the wickedest man in the world” by the John Bull newspaper

- Accused of Satanism (though he never identified as a Satanist)

- Denounced for his drug use, bisexuality, and radical views on sexuality

- Estranged from many contemporaries, including former Golden Dawn members

Crowley lived as deliberately and provocatively as he wrote, and the press of his time turned him into a sensational figure. The tabloid John Bull famously branded him “the wickedest man in the world”, a phrase that has followed him ever since.

His open embrace of bisexuality, his experimentation with drugs, and his radical writings on sexual freedom scandalized polite society in Edwardian Britain. Newspapers routinely portrayed him as a degenerate, a Satanist, or even a criminal, despite the fact that Crowley never identified as a Satanist and, in fact, rejected the Christian worldview that gave Satan meaning.

These attacks were not limited to the press. Many of his fellow occultists, including former members of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, turned against him. Some saw his public provocations as dangerous to the survival of the esoteric tradition, while others bristled at his domineering personality and relentless ambition.

Crowley, however, often seemed to relish the outrage. He cultivated the image of “The Beast 666”, mocking the moral values of his age and using scandal as a stage from which to declare his philosophy of Thelema.

Yet this notoriety came at a cost. The scandals frequently overshadowed his serious contributions to esoteric philosophy and spiritual practice. For decades, Crowley was remembered less as a pioneering magician and more as a figure of infamy.

Only later did scholars and practitioners begin to separate the myth of “the wickedest man” from the substance of his writings, recognizing the depth of his influence on Hermeticism, ceremonial magic, and modern spirituality.

Later Life and Death

- Lived across Europe and the U.S., struggling with heroin addiction

- Continued writing prolifically; his works include Magick in Theory and Practice, The Book of Thoth (Tarot), and Magick Without Tears

- Died in 1947 at the age of 72 in Hastings, England

After the closure of his Abbey of Thelema in Sicily and his expulsion from Italy in 1923, Crowley spent the rest of his life moving restlessly between France, Germany, England, and the United States.

He lived in near-constant financial precarity, often relying on patrons, students, and publishing ventures to survive. During these years he also struggled with a profound heroin addiction, originally developed as a treatment for his chronic asthma. Despite repeated attempts to quit, the addiction marked the last decades of his life and further fueled his reputation as a scandalous figure.

Yet Crowley never ceased to write. His later works show both the refinement of his magical system and his enduring creativity. Magick in Theory and Practice stands as a cornerstone of his teaching, laying out his comprehensive vision of ceremonial magic.

The Book of Thoth, created in collaboration with Lady Frieda Harris, combined his symbolic commentary with her striking artistic designs to produce the famous Thoth Tarot deck, still widely used by occultists today. Toward the end of his life, he composed Magick Without Tears, a collection of letters to students in which he sought to explain his system with unusual clarity and directness, stripping away some of the deliberate obscurity of his earlier style.

Crowley died on December 1, 1947, in a boarding house in Hastings, England, at the age of 72. At his funeral, passages from The Book of the Law and his Hymn to Pan were read, prompting the tabloids to denounce the ceremony as a “Black Mass.”

His ashes were later sent to the United States, where they were interred by his disciple Karl Germer.

Legacy and Influence

- Thelema remains a living tradition, practiced worldwide

- Inspired Wicca (Gerald Gardner incorporated Crowley’s material)

- Influenced the 1960s counterculture, psychedelic spirituality, and chaos magic

- Revered by artists and musicians—his face even appears on The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album

Crowley’s influence on modern spirituality is enormous; in fact, it’s almost impossible to do anything in the western esoteric tradition that doesn’t have Crowley’s fingerprints on it. For the record, though, Crowley, while a true master of his craft, was more a synthesizer of ideas than a founder father, that honor would go to his early Hermetic brethren, Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers and Allan Bennett.

But unlike his peers, Crowley was a brand. He wasn’t afraid of controversy, he knew all press, to some extent, was good press, because it allowed him to more easily find financiers in the latter part of his life, once his inherited funds had dried up.

Where to Start with Crowley’s Work

For seekers curious about his teachings, key texts include:

- 📘 Magick in Theory and Practice – A practical manual of magic

- 📘 The Book of Thoth – His esoteric commentary on the Tarot

- 📘 Magick Without Tears – A collection of letters explaining Thelema